Juror

© 2022 Victor Cabana

She was the 54th.

All eyes flicked up and locked on her, transfixed, as she eased through the swinging doors. Every whispered, polite conversation between strangers fell silent mid-sentence, all cellphones suddenly became uninteresting, and the air thinned as the unison, awed inhalation intensified the utter silence.

Flat-out gorgeous.

As she surveyed the gallery of the courtroom, the gallery breathlessly surveyed her.

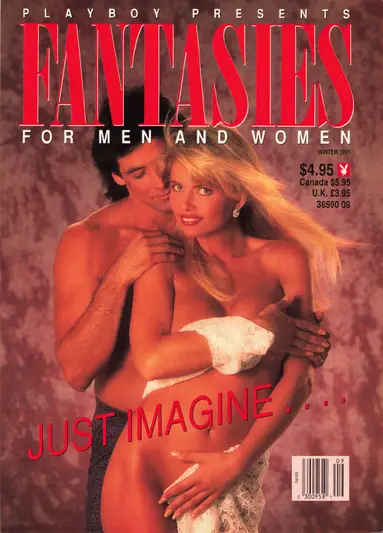

Statuesque. Five-ten minimum, probably late twenties, stunningly attractive. Long, lustrous, naturally wavy burnt-toffee hair cascaded freely over her shoulders and framed her thin, regal face, suggesting lineage to generations of czars. Sunken cheeks, inverted Nike-swoosh eyebrows over compelling blue-grey eyes, strong nose, and luscious lips that began paper thin at each end and blossomed to a voluptuous pouty pucker. Her long, savory neck -- it simply invited nibbles -- was adorned by a single strand of perfect pearls. Broad shoulders made her narrow waist seem even more so, as did her temptingly full, curvaceous hips.

She was stylishly, if a bit provocatively, dressed in a tight white silk blouse with the top two buttons undone. Hints of her white lace brassiere showed through the sheer fabric, stretched taught over perfect, succulent breasts. Her dark navy skirt, ending just above her knees, hugged toned curvaceous thighs, and white stockings clung to her taut, shapely calves and tapered down to spike-heeled, black leather boots. Their red sole and buckle gave the pedigree and spoke volumes: Louboutin, haute couture, and, along with the pearls, money. Lots of money.

The only remaining seats in the courtroom gallery were on the benches in the far corner, and she made for them. Two hopefuls -- under truth serum every straight male regardless of age would confess to instant, outlandish erotic fantasies -- stumbled awkwardly up and tried to scootch together the suddenly unimportant fellow occupants of their benches. Making room for her. Next to them. She gave them the disregard they deserved and floated -- I'd thought her wonderful thighs might betoken running or soccer, but the grace with which she moved meant she was a dancer -- to the center aisle, then to the empty seat next to an elderly woman in the back row.

No such commotion attended the arrivals of potential jurors 55 through 60, and we all resumed our chosen modes -- chatting amiably, stewing silently, or finding our phones fascinating as we cooled our heels. I admired the large portraits of past judges for the Northern Judicial District of Illinois. Crusty, well-dressed, old white guys, to a man.

The Clerk of Courts deigned to drop in 22 minutes later. We sixty citizens, who volunteered for jury duty by foolishly registering to vote, we who were to sit in judgement of our peer, had been required to arrive by 8:15. Under penalty of law. So we could sit, idly, until 8:43 when the Clerk told us that we would be compensated $50 for our time, plus mileage. Also lodging, if and only if we lived more than 60 miles away, and then only up to $97.66 or actual expense, whichever was less.

The Clerk then informed us of our duties and gave an overview of the case. The defendant was charged with conspiracy to commit murder and racketeering -- bootlegging, extortion, and other nefarious practices -- under RICO, the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act. It meant one thing: the mob. The Clerk then gave each of us a numbered card, from 1 through 60, as randomly chosen as we had been from the registered voter rolls of the federal court district. The cards would allow the judge and attorneys to refer to us jurors by number, rather than by name.

I held my breath as the numbers were dolled out. I had many work-related balls in the air and being tied up all day for the anticipated two weeks of the trial would not help my juggling act. Not at all. Numbers 1 through 12 took seats in the jury box. The next 12 were invited to sit on folding chairs set up in front, and the rest of us got to return to our benches. I was thrilled to get 51. It seemed pretty safe, as 39 others would have to be dismissed before I moved up and got one of the "special" seats.

The prosecutors, defense attorneys and the defendant had moseyed in randomly before 8:55. We all rose when Judge Martha Trimble came in precisely at 9:00, then once again when she administered our oath. She introduced herself and had the attorneys introduce themselves. When the lead defense attorney presented his client I couldn't see his face, but I did see wealth and power. His pale gray pinstripe suit fit perfectly, which meant tailoring and exact fitting. Made just for him.

In old French Voir dire means "true say," and it then commenced. Jurors 1 through 24 took turns, in numerical order, giving answers to the many questions printed on the back of their numbered cards. It amounted to giving their life histories. Those of us in the gallery were instructed to formulate our answers to the same questions on the back of our cards, and to pay close attention to all further queries.

Three of the first 24 were dismissed for cause. One had peculiar religious views, and two knew one of the lawyers, people associated with the accused, or one the many witnesses to be called. Jurors 25, 26, and 27 took their places in the jury box or on chairs in front. I still felt good. Surely I was safe.

Then the defense attorney had his turn. Peremptory challenges removed three more. My confidence continued to ebb when the leading questions from the defense team became curiously intrusive. When asked if they had ever done, known, thought, felt, or imagined x, y, or z, juror after juror raised their hands and were dismissed.

Lucky me, I got to replace original juror # 24 when she was excused and left the courtroom. By answering the questions on the back of my card I gave my life story, and then answered all previous follow-up questions. Truthfully. This was serious. I have never shirked my duty, and I wasn't going to lie to avoid service.

At the end of voir dire there were 24 of us left in the chairs and the jury box. Still I thought my odds were decent, 50 -- 50. Surely, twelve others would be more acceptable than me.

Then we cooled our heels again while the prosecution and defense teams took turns eliminating those of us they didn't want, trading off, each side crossing off one number, then passing the sheet to other team. When they were done, the judge began to read the numbers of the winners, those who would remain, hear all the evidence, and decide the case. She began with the lowest number, # 1 -- the lucky fellow had his number called and thus he got a seat on the jury -- and I kept track, hoping twelve would be seated before the judge got to me. I didn't count using my fingers, though. They were crossed.

10 jurors had been seated when all the numbers below 50 had been called. I cheered silently when 50 got a seat, and made an ardent appeal to the deities: let the judge skip 51. Please. The gods answered my fervent prayer with mocking laughter. I was so stunned to hear Her Honor intone "51" that I wasn't even aware of the last number read, that of the lucky soul who would get to attend the whole trial, hear all jury instructions and deliberations, but would not be able to say or do anything. The alternate would only become active if another juror became ill or was somehow disqualified during the trial.

We all rose as the judge exited after telling us to return after an hour recess for lunch. After which the trial would begin. Once outside I booted up my phone -- they had to be off in the courtroom -- and called my assistant. The dark, angry late-September skies and whipping, stinging gusts perfectly matched my mood, and I tried, hard, not to snarl at Marge as I informed her of the disaster. I asked, well, instructed, her to cancel, or reschedule for evenings, all my meetings, and to get the files for my new accounts and upcoming visits together so I could pick them up tonight. After my usual Caesar salad with broiled salmon for lunch, which, maybe due to my mood, tasted like dross, I moped back into the courtroom.

I found that seat # 12 was in the corner of the back row, right next to the alternate's chair. The storm clouds parted slightly when I saw a possible upside to my situation. She was the alternate juror. She smiled as I sat next to her. To my friendly"Hi," she told me her name, Katrina, and I said I was Frank.

Which wasn't quite true. My Francophile mother had named me François, and later shortened it to Franç, spelled Franc and pronounced "France." My kindergarten teacher said it with a hard C, and Franc became Frank. When I tried to correct her, the other kids made it into Francie, which rhymed with all manner of neat words, and Frank suddenly seemed better. Call me Frank.

After the chief prosecutor was done with her opening statement it was clear that the case would be easy. Open and shut. Anthony "Tony" Galliano was a Chicago mafia underboss. We would hear from the legal wiretaps and confessions of underlings, that Tony had ordered the killing of an unfortunate night club owner who stupidly refused to pay for protection. Both the hood that pulled the trigger and the one who drove the getaway car had flipped on Tony, and would testify as to Galliano's direct involvement. Excellent, I thought. We'll be done in two days.

However, as the lead defense attorney's first sentence slithered off his serpentine silver tongue, I recalled the time Jacob, my lawyer cousin, once regaled me with the defense lawyer's creed: if the facts are against you, argue the law; if the facts and the law are against you, put everyone else on trial. Throw shit against the wall and see what sticks.

Tony Galliano was completely innocent. It had been entrapment by the FBI; the witnesses were admitted liars, felons, and murderers trying to get reduced sentences; the warrants for the wiretaps were illegal; the president of the United States hated Tony and demanded that his attorney general prosecute him because Tony had bested him in legitimate business; the deceased had actually hired the hit man himself so his family could get the insurance. Etc., etc. Katrina leaned closer to me and murmured, sotto voce, "I've never seen such an innocent man," then sat back and giggled softly. I smiled and basked in her perfume. I liked it. A lot.

After the mid-afternoon break my considerable relief -- I still harbored hopes for a speedy trial, meaning I could return to my job -- lasted only until the prosecutor asked to speak with the judge in chambers. Judge Trimble looked grim when she returned, and even less happy when she informed us that death threats had been made. Against jurors. Accordingly we were going to be protected, sequestered, locked away in a hotel under armed guard. The trial would resume tomorrow at 9:00 AM. Now we would be accompanied by law enforcement as we drove our vehicles home, packed a bag, and were transported to our new lodging.

**

"Leave it off."

Having been entranced by it all afternoon, it was Katrina's scent as much as her sultry voice that froze my hand just an inch from the light switch.